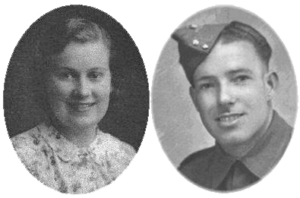

Frank

I came to England with the Canadian Army in November 1941. My Regiment was 13th Canadian Field Regiment Artillery. We knew for a long time that we would be landing with the assault troops on D-Day, though of course we did not know when or where. A lot of our training was done on Studland beach because it was similar to the beaches we were to land on in France. We were trained on the 25-pounder field gun, but shortly before D-Day these were changed to the SP (self-propelled gun) with a 105mm gun and also a 50mm gun mounted on a tank chassis with an open top, using American ammunition.

About two weeks before the big push, the entire Regiment was put behind a barbed wire cage so that we were completely cut off from all contact with the outside world; this was at Parkgate near Southampton.

When orders eventually came through for us to leave the compound, we knew that things were on the move. All the tanks, ammunition, etc, were parked nose to tail for miles along the roadside waiting to head for the landing barges. Then without warning at about midnight, a lone German bomber flew over the convoy and dropped its load, hitting the tank in front of me and others. Ammunition was soon exploding everywhere. Tank drivers who could move their tanks did so to a safer place even though some were on fire. A large amount of armoured equipment was thrown a considerable distance by the explosion and a motorcycle was blown some 800 yards away. Also, a number of houses were destroyed but no one was killed. The toll for the night was two Sherman tanks, four SPs, a Jeep and three motorcycles all of which had to be replaced and waterproofed before we could load.

We loaded onto the barges at Gosport on 1 June, packed tightly together and then moved into Stokes Bay where the Navy put a camouflage net over the tank landing craft, which were flat-bottomed and open to the weather. There was little room to move and everyone was stiff. We stayed there until 5 June and the weather was appalling during this time. I learned to play chess to pass the time away and keep my mind from what lay ahead.

When the nets were removed from above, we knew that all the months of training we had done, firing onto beaches, would soon be for the real thing. As we sailed down the Solent, we passed some Royal Navy destroyers and the men ran to the saluting stations to honour those who would make tomorrow history.

Our Regimental Padre conducted a short Service and led the singing of Abide With Me, which quite upset me, as I was leaving behind my wife who was expecting our first baby at any day.

The weather had improved slightly but it was still very rough, and everyone was seasick with the vomit and the waves splashing over the side onto the steel floor, which made it a job to stand up. I am sure no one got any sleep.

It was now the morning of 6 June and we had been told that we were landing on JUNO beach, on an uncleared minefield and that 50% casualties were expected.

There were ships, large and small, as far as the eye could see and we soon got our orders to fire, so at 1100 yards from the shore the guns of the Regiment opened fire onto the beach and all hell broke loose. As soon as the shell was fired, the case was thrown overboard. Shells were falling all around, no time now to be scared, the infantry had already landed, but the big guns in the German pillbox were trying hard to prevent the artillery from landing. At 200 yards from the shore, we were ordered to empty all guns and the landing craft turned back out to sea. HMS Rodney was called on to silence the pillbox. On the second run, I saw a Navy rocket ship fire a bank of 120 rockets and hit a plane flying across and they cut right into it. I saw the pilot’s parachute open; I have often wondered if he survived.

I was the tank driver and we tried to get off the beach as quickly as possible to allow others to get ashore. There was a lot of German bombing and strafing, but our casualties on JUNO beach were not as high as expected.

I can’t begin to express the feeling of seeing so many dead, all young men in the prime of life, you could distinguish the Germans by their helmets; all somebody’s boys.

Once we had landed, we made good headway and I believe got further inland than any of the other beaches. When we did finally stop, guards were put out and men sent on search duty as soon as the password was given.

D-Day was certainly a long, hard day and I defy any man to say he wasn’t frightened.

Much harder fighting lay ahead until Caen and Falaise were captured; it was very hard at Carpiquet airfield, which changed hands more than once. I was there when my son John was born.

I should have mentioned that each SP tank dragged behind it a metal sled called a Porpoise, containing infantry and artillery ammunition. The contents of the sled were thoroughly protected from moisture by waterproofing; yet there was some fear of ammunition exploding due to the amount of heat created by the metal rubbing along the cobble stone road. As it was, the bottoms of some were worn through when the tanks reached the first regimental position.

I forgot to mention that my first wedding anniversary was spent separated from my wonderful wife Molly. We were married on 14 June 1943, at the church of St Peter’s, Ardingly, West Sussex.

There were no mobile phones then so my wife could not contact me to tell me that I was a father for the first time when our son was born on 18 June 1944. As it turned out I would not ‘meet’ my son for another 7 months.

Molly

I can remember D-Day, 6 June 1944, as clearly as if it were yesterday. I hadn’t heard anything from my husband since he returned from a 24-hour leave 10 days or so beforehand, and neither did I know that when he returned from leave, his entire Regiment were put behind a barbed wire compound and cut off from any contact with the outside world. But I did know that when the invasion happened, he would be going in with the assault troops.

Our first baby was already two days overdue on 6 June and I hoped against hope that his daddy would be able to see him when he was born, but it was not to be. I got up that morning to hear that landings had been made on the beaches of Normandy and the bottom dropped out of my world. Our son wasn’t born until the 18 June, and at that time I hadn’t heard if my husband was still alive, but he was one of the lucky ones.

Our son John was 7 months old before he saw him for one precious week’s leave and 15 months old before he came home to us permanently.

Celebrating our Golden Wedding Anniversary on 14 June 1993.

Our wedding day at the church of St. Peter’s, Ardingly, West Sussex, 14 June 1943.